Understanding Why AGI Still Feels Distant

· 9 min read

Intro #

I’ve written a lot about artificial intelligence, lately. Those posts were mostly philosophical ponderings on AI’s impact on work, but lately I have found myself thinking more and more about how the general public understands AI, and about whether or not we truly are on the cusp of artificial general intelligence (AGI).

The prospect of intelligent machines has fascinated me for well over a decade. It started back in high school when I got my hands on Bostrom’s Superintelligence and Kurzweil’s The Singularity is Near and found myself enamoured by the possibility that AGI was on the horizon. As a result, over the past few months, I have had to grapple with a single question: if I have always wanted humanity to invent thinking machines, why am I finding it so hard to believe that we’re on the cusp of actually doing so?

In this post, I will put forward my grounded understanding of how modern machine learning works, and why, to me, AGI still feels quite distant.

The Illusion of Intelligence #

Let’s start with a simple thought experiment. Let’s say I show you this sequence of numbers:

+-----+ +-----+ +-----+ +-----+ +-----+

| 2 | | 4 | | 6 | | 8 | | ? |

+-----+ +-----+ +-----+ +-----+ +-----+

You’d probably say the next number is 10. But, what actually happened in your brain? You recognised a pattern (adding 2 each time) and applied it to predict the next value. This is similar to what machine learning does, but with astronomically more dimensions and parameters. Unlike humans, though, most ML systems can’t entertain multiple hypotheses or reason about alternative rules. They simply latch on to the statistically dominant pattern in their training data.

2 ── 4 ── 6 ── 8 ── ?

Human: recognizes rule (+2)

ML: fits statistical pattern in data

So, when we say an ML model “learned” to recognise cats in images, what really happened is that we fed it thousands of (labelled) images of cats, and through iterative mathematical optimisation, it found patterns in pixel values that correlate with the presence of cats. The model doesn’t “see” a cat any more than a calculator understands arithmetic.

Pattern Recognition as Function Approximation #

At its core, machine learning is about finding mathematical functions that map inputs to outputs based on example data.

Let’s say we want to predict house prices based on square footage. In traditional programming, we might hardcode something like:

def predict_price(sqft):

return sqft * 150 # $150 per square foot

But, what if the relationship isn’t linear? What if other factors (e.g. location, number of bedrooms) matter? This is where ML shines. Instead of us trying to figure out the exact mathematical relationship, we let the algorithm discover it.

graph LR

A[Inputs x] --> B["f(x) ≈ y"]

B --> C[Predicted y]

An ML model is essentially trying to approximate some unknown function f(x) = y, where x is our input (house features) and y is our output (price). The “learning” part is the mathematical optimisation process that adjusts the function’s parameters to minimise prediction errors on the training data. However, the model doesn’t discover the “true” underlying relationship, only the one that best fits the samples it has seen.

The Math Behind the Magic #

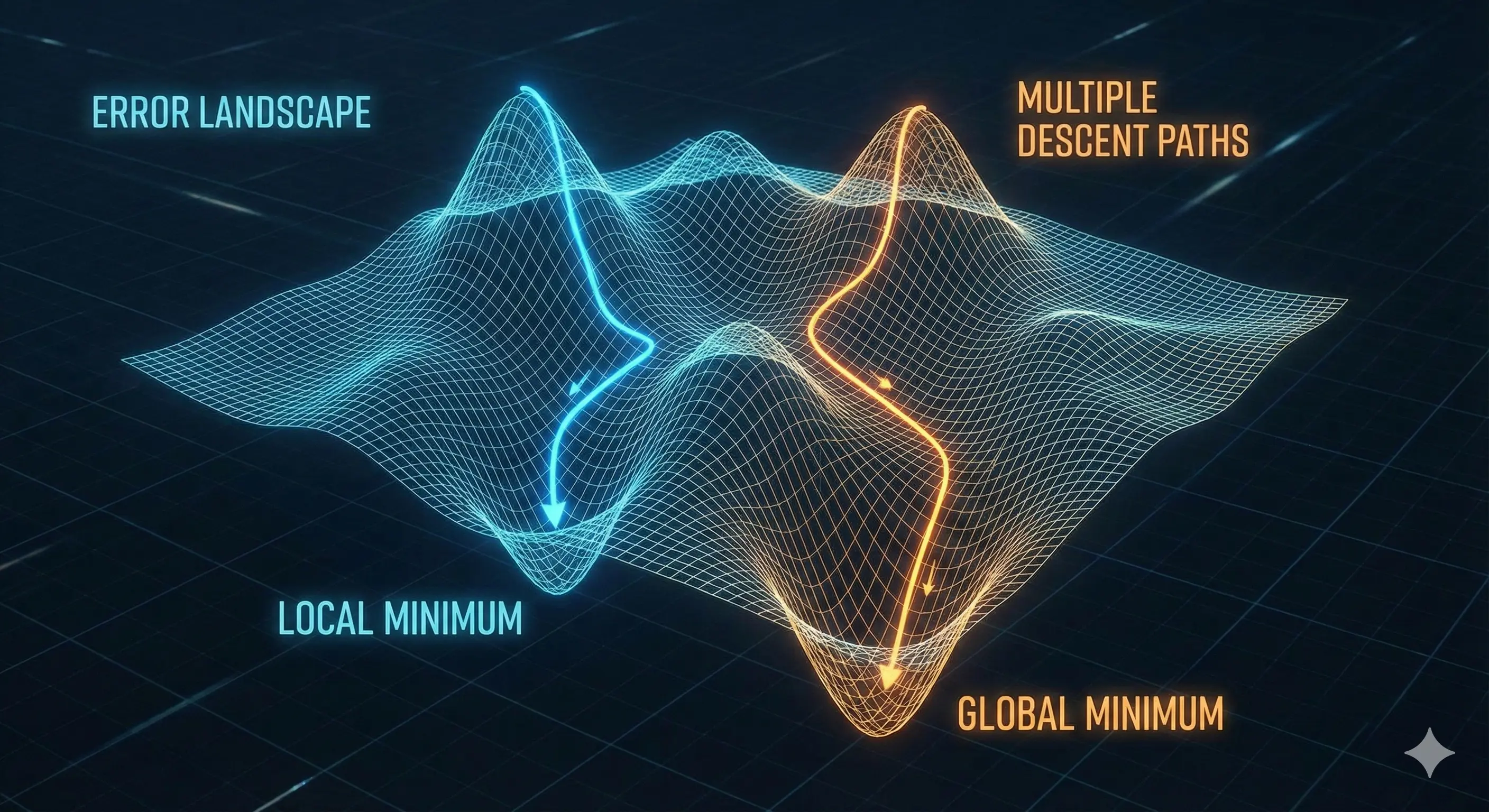

One of the fundamental concepts of ML is gradient descent. Imagine you’re blindfolded on a hilly landscape and trying to find the lowest point. You’d feel around with your feet, take steps in the direct that slopes downward most steeply, and eventually reach a valley. Gradient descent works similarly, except instead of physical terrain, we’re navigating through mathematical error landscapes with potentially millions of dimensions. And, it doesn’t guarantee the overall lowest valley, just a valley that reduces error.

But, this raises two crucial question: how does the model know how wrong it was? and, in a complex neural network with millions of parameters, how does it know which ones to adjust?

The how wrong part is handled by loss functions. These are mathematical formulae that convert the difference between predictions and reality into a single error score.

The “which parameters to adjust” part is where backpropagation comes in. This algorithm works backwards through a neural network using the chain rule in calculus to figure out how much each parameter contributed to the final error. It does so by simply computing numerical gradients and doesn’t provide any conceptual explanation or reasoning.

Together, gradient descent and backpropagation solve the fundamental challenge of ML: how to automatically improve a mathematical function based on examples.

Neural Networks are mostly matrix multiplication #

Neural networks sound incredibly complex, but let me let you in on a secret: they’re essentially chains of matrix multiplications with some non-linear functions sprinkled in. The biological metaphor is mostly marketing; what’s actually happening is linear algebra.

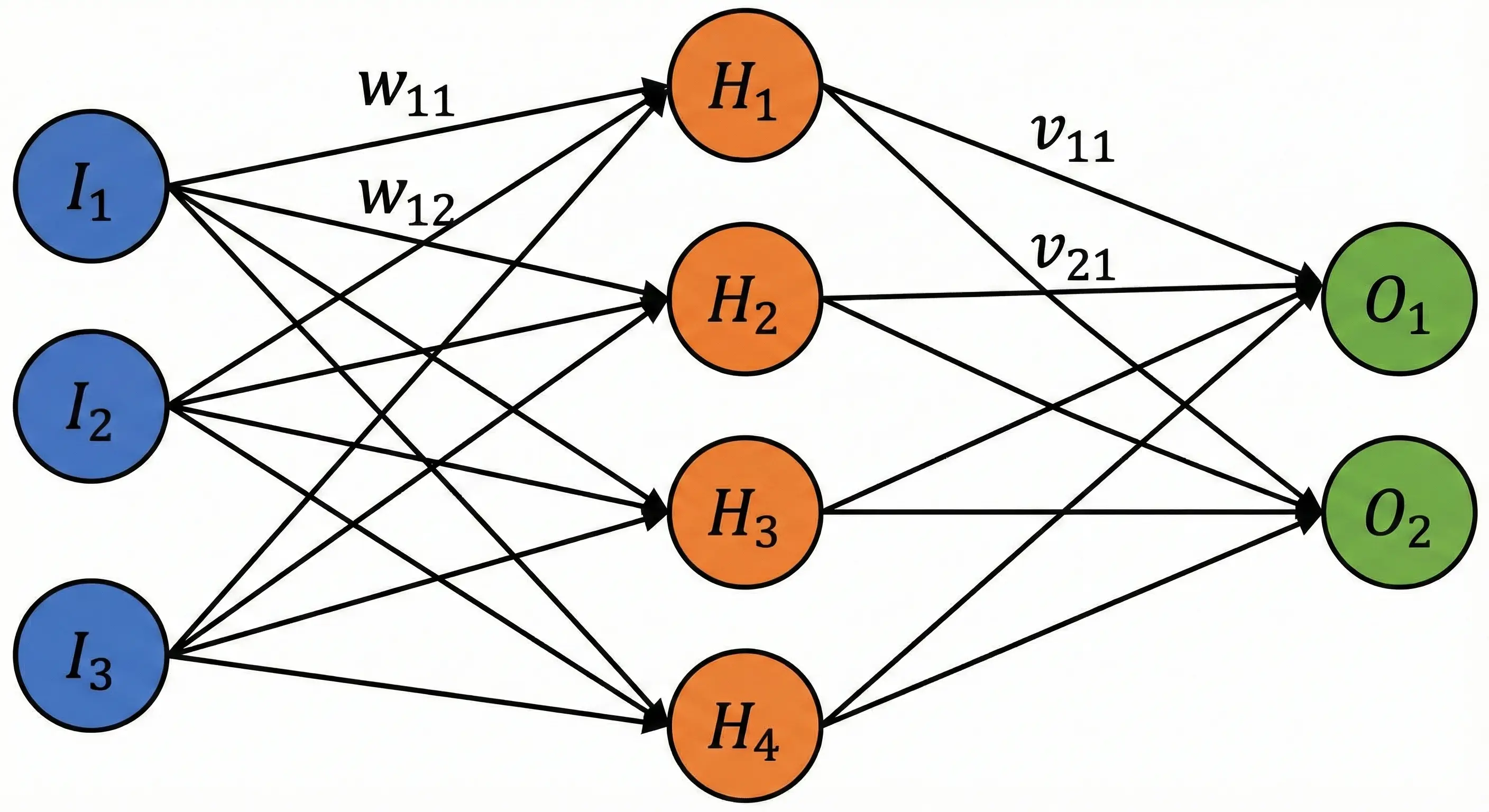

A simplified neural network looks like this:

Each neuron computes a weighted sum, adds a bias, and passes it through a non-linear activation function. Without those nonlinearities, the entire network would collapse into a single linear transformation. So, the magic isn’t the layers but the combination of matrix multiplication and nonlinearity.

Why This Matters for Understanding AI #

When models like GPT generate text, they’re not “thinking”. They are performing complex matrix operations over embeddings to predict the statistically likeliest next token based on patterns in massive amounts of text.

As we have seen over the last 3 years, this works astonishingly well, but remains patterns recognition rather than understanding.

Interpolation vs Extrapolation #

graph LR

A[Training Data Region] --> B[Interpolation OK]

B --> C[New Case Far Outside]

C --> D[Model Fails]

But, something I don’t feel gets enough attention is this difference between interpolation and extrapolation, even though it explains both the strengths and failures of today’s AI systems.

Interpolation is making predictions within the space covered by the training data. If a model has seen thousands of pictures of cats from different angles in different lighting, it can reliably identify another similar cat. Similarly, if a language model has “read” millions of news articles, it can produce something that sounds like a news article.

Inside the world it knows, the model performs impressively because it is recognising patterns it has statistically encountered before. Deep learning is superb at interpolation.

Extrapolation, on the other hand, is predicting something outside the kinds of examples the system was trained on. We humans do this constantly. We can apply a rule to a new situation we have never seen before, reason about causes and effects outside our direct experience, or learn from one example and generalise to many.

Current AI systems cannot reliably do this.

Ask an LLM to reason through a multi-step puzzle with a twist it hasn’t seen before, and it breaks down. That’s why with every new model release, you see many people sharing instances of how they flummoxed the model by asking it something weird and unfamiliar.

graph LR

A[Training Text] --> B[LLM: Pattern Model]

B --> C[Plausible Output]

C -. No reality verification .- X[World]

Knowing this distinction - where ML systems excel and where they struggle, allows us to understand, for example, why LLMs hallucinate, why self-driving cars fails in unusual conditions, and why vision systems falls for adversarial noise.

The Three Pillars of Modern ML Success #

Yet, we’ve got these remarkably intelligent-seeming systems that have become central to our daily workflows. How did we get here?

- Massive datasets: we’re not that much smarter about algorithms than we were 20 years ago, but we have exponentially more data. Sometimes models succeed simply because the dataset is so large that memorisation becomes surprisingly effective.

- Computational power: Training modern models requires GPU farms that can perform trillions of operations in parallel. The core math hasn’t changed; only the scale has.

- Better optimisation techniques: Innovations like batch normalisation, dropout, and attention mechanisms help stabilise training and improve generalisation. They reduce brittleness but don’t add understanding.

LLMs: Predicting Text with Style #

The current AI boom is largely driven by large language models (LLMs) like GPT, Claude, Gemini, etc. These models are powerful next-token predictors trained on huge text corpora. They have convinced many people that we are on the cusp on achieving AGI, but this isn’t a problem that can easily be solved by scaling. You can’t just throw more data at the problem and hope intelligence somehow manifests.

Really, prediction isn’t understanding. For example, a model can write about heartbreak without ever having experienced it. What it has done is absorb statistical patterns about how humans write about heartbreak. They can encode a surprising amount of world knowledge with no mechanism to validate whether those internal associations correspond to reality. And, this is why hallucinations continue to be an issue with LLMs: the system is rewarded for being plausible, not necessarily correct.

The Transformer Architecture #

The breakthrough that enabled modern LLMs is the transformer architecture, particularly the attention mechanism. Without diving too deep into the mathematics, attention computes similarity in a learned embedding space, enabling the model to draw connections between distant tokens. In a slightly oversimplified way, think of it as the model weighing the importance of different words in a sequence when predicting the next word (as opposed to just the last word as previous systems did).

The famous paper Attention is All You Need (PDF download) showed that this mathematical mechanism could capture long-range dependencies in text more effectively than previous approaches. But, again, it’s still mathematical correlation, not understanding.

Why This Perspective Matters #

I’m not trying to diminish the impressive capabilities of modern AI systems. The mathematical achievements are genuinely remarkable, and the practical applications are transforming industries. But I think approaching this from a place of understanding helps us think more clearly both about the possibilities and limitations of current AI.

If I were to summarise it, I’d say current AI is good at:

- Pattern recognition at scale

- Interpolation within its training distribution

- Producing fluent text based on learned correlations But struggles with:

- Robust reasoning

- Causal understanding

- Extrapolation beyond training data

- Consistent logical behaviour

- Explaining its own decisions

These limitations matter profoundly when deploying AI in real-world settings.

Conclusion #

Machine learning isn’t magic, and machines don’t think. But the mathematics behind modern AI is profound, and the engineering is remarkable.

As we continue to integrate AI into more aspects of our lives (voluntarily or otherwise), we need more people who understand what’s actually happening under the hood. This way, we can make more informed decisions about where and how to use AI systems, and make sure that they are aligned with human needs.

The next time someone tells you that an AI system “learned” something, remember: it computed its way to a statistical approximation of a function. And, honestly? That might be even more impressive.

Resources #

What is Backpropagation? | IBM

The Most Important Algorithm in Machine Learning

Gradient descent, how neural networks learn | Deep Learning Chapter 2